“The painful stories of the suffering of the African American community, in particular, remain hidden. Often, American Christians may even deny the narrative of suffering, claiming that things weren’t so bad for the slaves or that at least the African Americans had the chance to convert to Christianity. The story of suffering is often swept under the rug in order not to create discomfort or bad feelings.” — Soong-Chan Rah

I’ve lived in New York City for 11 years and first lived here for a summer 14 years ago. Since that summer, I’ve always been in love with this city, and did everything I could to get back here permanently. Fortunately, in 2010, my wife and I were able to do just that.

Though I like to think of myself as a student of the history of New York, especially my neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen—and for the last eight years I’ve strived to grow in the work of antiracism—I must admit that up until recently, I had no idea how pervasive the institution of race-based chattel slavery was here.

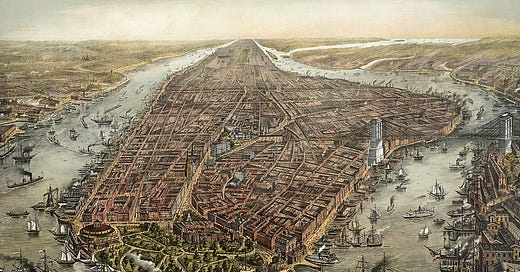

As the New York Historical Society puts it, “New York has preeminently been the capital of American liberty, the freest city of the nation—its largest, most diverse, its most economically ambitious, and its most open to the world. It was also, paradoxically, for more than two centuries, the capital of American slavery.” Ned Benton of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice confirms this, noting that the start of slavery in New York was sometime in the mid 1620s and ending in the late 1820s. NYC Urbanism adds a few more specifics: “Slavery was introduced to New York City when the Dutch settled the colony, bringing with them 11 African men in 1626 and three women in 1628. When the English captured the city in 1664 nearly 9% of the 8,000 settlers were Africans (slaves and freed) and their ownership was transferred to the British who institutionalized slavery, classifying them as chattel that worked involuntarily. In British New York City, killing a slave was illegal, but unlike the Dutch who had allowed slaves to marry in church, under the British they could not be married and families were split up.”

The Historical Society reports that during the colonial period of our country, 41 percent of households in New York City owned slaves, compared with 6 percent in Philly and 2 percent in Boston. “Only Charleston, South Carolina, rivaled New York in the extent to which slavery penetrated everyday life.”

In a lot of ways, the life of the enslaved African in New York City looked different than in Charleston or elsewhere in the South; according to The New York African Free School, “Although New York had no sugar or rice plantations, there was plenty of backbreaking work for slaves throughout the state. Many households held only one or two slaves, which often meant arduous, lonely labor. Moreover, because of the cramped living spaces of New York City, it was extremely difficult to keep families together. It was not uncommon for owners to sell young mothers, because they did not want the noise and trouble of children in their small homes.” The Historical Society also notes:

Slaves constructed Fort Amsterdam and its successors along the Battery. They built the wall from which Wall Street gets its name. They built the roads, the docks, and most of the important buildings of the early city—the first city hall, the first Dutch and English churches, Fraunces Tavern, the city prison and the city hospital.

Slavery was no milder in the urban North than in the Deep South. Instances of abusive treatment permeate public and personal records. The city's Common Council passed one restrictive law after another: forbidding Blacks from owning property or bequeathing it to their children; forbidding them to congregate at night or in groups larger than three; requiring them to carry lanterns after dark and to remain south of what is now Worth Street; threatening the most severe punishments, even death, for theft, arson, or conspiracy to revolt—and carrying out these punishments brutally and publicly time and again.

Officially, slavery ended in New York in 1827, though the reality of the institution did not disappear in the city. “While New Yorkers were not allowed to own slaves, the Port of New York allowed slave ships to anchor and restock,” Benton explains.

In other words, the system may have changed and even been abolished, but the narrative remained strong. This was obvious not just in the ships that benefited from the Port of New York, but also in the Civil War draft.

As Newsweek’s Alexander Nazaryan writes, “The draft began in New York City about two weeks after Gettysburg. The draft would do what all drafts do, which is compel men who do not have the natural constitution of a warrior to become one anyway. You could avoid it by paying $300. Otherwise, you would don the Union blue.”

The draft led to riots that were centered around race; Irish New Yorkers had no interest in serving alongside their free, Black neighbors. On July 14, 1863, The New York Times published a haunting telling of the riots

Among much destruction, many Black New Yorkers were murdered. “There were probably not less than a dozen negroes beaten to death in different parts of the City during the day,” the Times reported. “Among the most diabolical of these outrages that have come to our knowledge is that of a negro cartman living in Carmine-street. About 8 o’clock in the evening as he was coming out of the stable, after having put up his horses, he was attacked by a crowd of about 400 men and boys, who beat him with clubs and paving-stones till he was lifeless, and then hung him to a tree opposite the burying-ground. Not being yet satisfied with their devilish work, they set fire to his clothes and danced and yelled and swore their horrid oaths around his burning corpse. The charred body of the poor victim was still still hanging upon the tree at a late hour last evening.”

Though freedom may have existed in New York City, the narrative of slavery remained strong.

But though it remained strong, what proved and continues to prove even stronger is the spirit of those for whom the narrative oppresses. I’ve learned of this in the history of Hell’s Kitchen and the former neighborhood of San Juan Hill. I’ve seen this in the history of churches like St. Benedict the Moor on 53rd Street. The Underground Railroad has a strong history in New York City.

This is a history and reality of which I am undeserving and certainly unqualified to share, but also it is a history and reality that needs to be told and heard and celebrated.

Though far from complete, the New York Historical Society succinctly describes this reality as it relates to the history of slavery in our city; you can read it here. These hopeful truths are important and critical because the deepest, darkest moments of our history don’t negate the incredible, earth-changing resilience, perseverance, strength, and faith of our Black brothers and sisters.

So why am I sharing all of this?

Largely, this is helping me process the history of the city that I call home, and the city in which we’ve planted a church that seeks to be antiracist. It also confirms to me the necessity of this antiracist work today. Just as in the 1800s, though slavery may not exist in New York City in 2021, the narrative of white supremacy still runs through our streets. This is evident in the reality that this history of our city is largely untold, at least in the white, evangelical circles that I was part of.

Perhaps more than anything, though, I share this as a lament.

As I’ve grown as a preacher over the years and as a lover of New York history, I’ve often said from the pulpit how our city was founded on the exchange of money and the trading of commerce. I’d then make a weak attempt to relate that to our struggle for money today, and then paint a rosy picture of some type of faith and work theology. What I never said, and never even considered, was that the exchange of money and the trading of commerce included the buying and selling of Image Bearers, followed by their physical, relational, spiritual, and emotional oppression.

I lament this history and I lament my ignorance of it. I lament my privilege of never even having to consider it. How can we mention Wall Street in a sermon without acknowledging that it wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for the unpaid, brutal labor of enslaved brothers and sisters? How do we talk about modern-day criminal justice reform and neglect to repent of the fact that New York City’s first prison was built by Black men and women?

My heart is anguished as I write this. I hope that we confront this history with the intent of allowing it shape us today and tomorrow, so that one day the narrative of white supremacy can be, once and for all, destroyed.

“In the American Christian narrative, the stories of the dominant culture are placed front and center while stories from the margins are often ignored. As we rush toward a description of an America that is now postracial, we forget that the road to this phase is littered with dead bodies. There has been a deep and tragic loss in the American story because we have not acknowledged the reality of death. Stories remain untold or ignored in our quest to ‘get over’ it. But in the end, we have lost an important part of who we are as a nation and as a church. We have yet to engage in a proper funeral dirge for our tainted racial history and continue to deny the deep spiritual stronghold of a nation that sought to justify slavery.” — Soong-Chan Rah

You can’t have a funeral without a death! Racism is alive and well in New York as in the rest of the USA. You are right the financial foundation of Amerikkkas wealth is the slave economy. The City Hall and the Court house are built on the graves of African peoples. Thank you for your honesty and search for truth. I too am a minister and look to God to in his own time end the hate. May all who seek him find his love!!

Good piece of history and the case for reparations; as legacy it birthed this country’s current racial imbalance, which was never paid up.